We're going to do a comparative genomics/proteomics experiment designed to explore amino-acid usage in a particular protein (DnaJ) across a couple dozen bacterial species. Even if you're not a bio-geek, I hope you'll follow along. At the very least, you'll learn how to make pretty graphs from any kind of data using the server at ZunZun.

What is the DnaJ protein, you ask? It's one of a class of proteins known as heat shock proteins, which are produced in response to elevated temperatures. (Your body produces heat shock proteins in response to fever, for example.) As you probably know (or can guess), proteins, in general, are rather sensitive to heat. Even a small amount of heat can cause a protein to start to unravel (or denature). DnaJ and its partners have the job of helping proteins re-fold into their correct original 3D shape(s) after exposure to heat. They're like little repair jigs. A partially damaged protein goes in; it re-folds and comes back out good as new.

Heat shock proteins occur widely, across all domains of life, and their amino-acid sequences are highly conserved; but they do differ. As we'll see right now.

Step 1

Go to http://www.uniprot.org/ and enter "DnaJ" (case doesn't matter) in the search field at the top of the page, then hit Enter. A list of organisms with DnaJ will appear, each with a checkbox on the left. Check all the checkboxes on the page (gang-check them with Shift-click).

Step 2

You'll notice at the bottom of the window there's a green bar with buttons "Retrieve," "Align," "Blast," and "Clear." Click the Retrieve button.

|

| Steps 1 and 2. |

Step 3

In the page that comes up, look for FASTA on the left. Under it are two links, Download and Open. Click Open. (See screen shot below.) You'll see a bunch of protein sequences (with one-letter abbreviations for amino acids), each preceded by a line that begins with > (greater-than sign). These are our DnaJ proteins.

|

| Step 3. |

Step 4

Click F12 to toggle open the console window. Be sure the Console tab is showing. In Firebug, you may also have to click the Console menu and choose Command Editor from the dropdown list.

Enter and execute (with Enter, in Chrome, or with Control-Enter in Firebug) the following lines of code:

all = document.getElementsByTagName("pre")[0].innerHTML.split(/>/);

all.shift();

It's important that the part between slashes be ampersand-g-t-semicolon, not a greater-than symbol. The browser is showing you greater-than signs but in the HTML markup it's really ampersand-g-t-semicolon, not angle brackets. We actually do want to split on >, not on >.

Note that to execute a line of code in Firebug you have to type Control-Enter. In Chrome, you just type Enter. But in Chrome's JavaScript console, you have to use Shift-Enter to type on more than one line.

The variable all now contains an array of protein sequences. If you want to verify it, type all.length (then Enter, or in Firebug Control-Enter), and you should see the length of the array, 25.

Step 5

Enter the following code in the console (and execute it with Enter; it'll do nothing, which is fine).

function analyze( item ) {

var sequence = item.split(/SV=\d\n(?=\w)/)[1];

var lysineCount = sequence.match(/K/g).length;

var arginineCount = sequence.match(/R/g).length;

lysineCount /= sequence.length;

arginineCount /= sequence.length;

console.log( lysineCount + " " + arginineCount );

}

This is the callback code we'll use to process every member of the all array. Each item in the array consists of a FASTA header followed by a protein sequence. We just want the sequence, not the header, which is why we have a first line that splits off the part we need. The remaining lines obtain the number of lysines (K) and the number of arginines (R) in the protein sequence, then we divide those numbers by the sequence length to get a frequency-of-occurrence. The final line prints the results to the console window.

This function, by itself, doesn't do anything until we run it against each amino-acid sequence in the all array. That's the next step.

Step 6

Enter the following line of code into the console and run it with Enter (or Control-Enter, in Firebug):

all.forEach( analyze );

The console should immediately fill with numbers (25 rows of two numbers each). That's our data. We need to graph it to see what it looks like. Ready?

Step 7

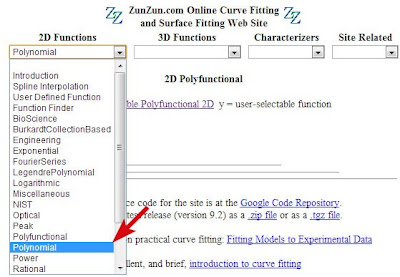

Go now to http://zunzun.com and notice four pulldown menus at the top of the page. Use the far-left dropdown to select Polynomial.

|

| Select Polynomial from the ZunZun function list. |

A new window appears with ugly (or beautiful, depending on your mindset) formulas. Click the link to First-Order (Linear) 2D. Why? Because in the absence of any foreknowledge, we're going to blindly assume that our data is best fit by a straight line. If it's not straight-line data, we can come back and change our selection later.

When you click the First-Order (Linear) 2D link, you'll quickly be in a stark-looking window with a single pulldown menu at the top. Click it and select Data Labels for Graphs. Replace "X data" with "Lysine" and "Y data" with "Arginine."

|

| Select Data Labels for Graph. |

Step 8

Now use the single pulldown menu to select Text Data Editor.

Quickly go back to that console window and Copy all of your data (all 25 rows of numbers), then Paste the data into the Text Data Editor box.

Click the Submit button near the top of the page. Be patient, as it may take up to 20 seconds or so for your graph to be ready.

You'll know your graph is ready when the window changes to one that shows four pulldown menus at the top. The far-right menu is Data Graphs. Click into it and select Arginine vs. Lysine with model. NOTE: The exact names of the menu items will depend on how you labeled your axes at the end of Step 7 above.

You should see the window change to a view of a graph that looks like this:

|

| Graph created on demand by the ZunZun server. |

Pretty easy, right? It gets better. The line that ZunZun drew through the data points is a regression curve that minimizes the sum of squared error. To see the formula for the line, including coefficients, use the far-left menu, called Coefficients and Text Reports, to select Coefficients. Don't worry, your graph will still be there when you're done. To get back to the graph at any time, just use the far-right menu and any of the commands under it (which re-display the graph in various ways).

The graph seems to be saying that Arginine levels go down as Lysine goes up. But how good of a correlation is this, really? Use the far-left pulldown menu again. This time select Coefficient and Fit Statistics. You'll notice a ton of stats (chi-squared and so on). Among them, r-squared is given as 0.637834788057. That means the correlation coefficient, r, is 0.799, which is pretty solid.

I'll save the interpretation of our experiment's results for another time. For now, notice that underneath your ZunZun graph are links for saving the graph either as PNG or SVG. I strongly recommend you save it as both. You can open SVG in both Photoshop and Illustrator (and most browsers too). You will definitely want to keep an SVG version around to edit by hand in your favorite text editor (SVG is just a variety of XML). I'll be showing you how to do lots of sexy things with SVG graphs in upcoming posts.